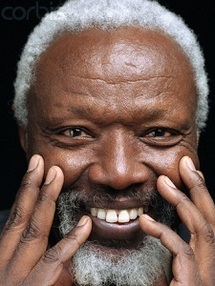

Léopold SéDAR SENGHOR

Biography :

Léopold Sédar Senghor (October 9,1906 -December 20, 2001), was a Senegalese statesman and first president of Senegal (1960-1980).

He became a teacher, writer, and politician, a member of the French

Constituent Assembly in 1945, deputy for Senegal in the French National

Assembly (1948–58), and president following his country's independence.

He also won several literary awards as a poet, and was the first black African to join the French literary institute, the Academie Francaise in 1983.

Leopold Sedar Senghor was not only president of the Republic of

Senegal, he was s also Africa's most famous poet. A cofounder of the Negritude cultural movement, he is recognized as one of the most significant figures in African literature.

Senghor was born in the predominantly Islamic province of Joal (Senegal), was raised as a Roman catholic.

The son of a prosperous landowner, Senghor was extraordinarily gifted in

literature and won a scholarship to study at the Sorbonne in Paris

(grad. 1935). There he met fellow writers such as Aimé Césaire and Léon Damas, with whom he formulated the concept of négritude, which asserted the importance of their African heritage .

He became a French teacher, served in an all-African unit of the French

army in World War II, and after the war represented Senegal (1945–58)

in the French legislature. He then held a series of offices in Senegal

and became one of the founders of the African Regroupement party.

Senghor was president of the legislative assembly in the Mali Federation

(1959) and, when Senegal withdrew from the federation (1960), he became

president of the newly formed Republic of Senegal.Senghor continued to work for African unity, and, in 1974, Senegal joined six other nations in the West African Economic Community. He was reelected president in 1963, 1968, and 1973, remaining in office until his retirement in 1980. He lived in Normandy (France) for most of the rest of his life. A distinguished intellectual and champion of African culture, he wrote numerous volumes of poetry and essays in French, including Chants d'Ombre (1945), written while he was interned in a Nazi prison camp; Hosties noires (1948); Chants pour Naëtt (1949); and Éthiopiques (1956). At the head of his many poems, Senghor indicates the musical instruments that should accompany them, illustrating his belief that the poems should become songs to be complete.

Achieving major success as a poet, politician, and intellectual, Leopold Senghor has had a truly unique identity among African leaders. His development from tribal member in Senegal, to scholar in France, to head of the government back in Senegal made him a symbol of Africa's shift from colonial domination to self- determination.

Along with maintaining dual identities as an African and Frenchman, Senghor has remained active as both a poet and a politician during his long career. Janet G. Vaillant summed up Senghor's life in Black, French, and African: A Life of Leopold Sedar Senghor: "Just as he [Senghor] refused to choose between his talents as poet and politician, sensing that each added depth to the other, so, too, he refused to choose between his two homelands, France and Africa. He knew their strengths and weaknesses, their darkness and their light, and he loved them both.

Senghor received several international awards as a writer and a major African political opinion leader, among others Dag Hammarskjöld Prize (1965), Peace Prize of German Book Trade, Haile Sellassie African Research Prize (1973, Apollinaire Prize for Poetry (1974). He was appointed in 1969 member of Inst. Français, Acad. des Sciences morales et politiques.

There it's one of the best poema of Leopold Sedar Senghor.

Night of Sine

By Léopold Sédar Senghor

Women, rest on my brow your balsam hands,

Your hands gentler than fur.

The tall palm trees swinging in the night wind

Hardly rustle. Not even cradlesongs.

The rhythmic silence rocks us.

Listen to its song, listen to the beating of our dark blood, listen,

To the beating of the dark pulse of Africa in the midst of lost villages.

Now the tired moon sinks towards its bed of slack water,

Now the peals of laughter even fall asleep, and the bards themselves

Dandle their heads like children on the backs of the mothers.

Now the feet of the dancers grow heavy

And heavy grows the tongue of the singers.

This is the hour of the stars and of the night that dreams

And reclines on this hill of clouds, draped in her long gown of milk.

The roofs of the houses gleam gently.

What are they telling so confidentially to the stars?

Inside the hearth is extinguished in the intimacy of bitter and sweet scents.

Women, light the lamps of clear oil, and let the children

In bed talk about their ancestors, like their parents.

Listen to the voice of the ancients of Elissa. Like we, exiled,

They did not want to die, lest their seminal flood be lost in the sand.

Let me listen in the smoky hut for the shadowy visit of propitious souls,

My head on your breasts glows like a kuskmus ball smoking out of the fire,

Let me breathe the smell of our dead,

Let me contemplate and repeat their living voice, let me learn

To live before I sink, deeper than the river, into the lofty depth of sleep.

Cheikh Anta Diop The "Black Pharoah"

On the 7th of February, 1986, Africa lost one of her illustrious sons, Cheikh Anta Diop, an exceptional African whose singular destiny and contributions were in tune with an Africa sometimes (promising), hopeful and some times despondent.

While leaving us, Professor Cheikh Anta Diop bequeathed to Africa a heritage of liberation without precedence: the knowledge of one's origin.

It would not strike the mind of any historian of the ancient Mediterranean

civilizations to deny the crucial role played by black Egyptian peoples,

in deed Ethiopians, in the development of sciences, arts, techniques,

and it was from distant antiquity. The idea of "black tabula

rasa", (Africa devoid of history (culture); in short, devoid

of humanity, dear to colonial histography is largely posterior.

It would not strike the mind of any historian of the ancient Mediterranean

civilizations to deny the crucial role played by black Egyptian peoples,

in deed Ethiopians, in the development of sciences, arts, techniques,

and it was from distant antiquity. The idea of "black tabula

rasa", (Africa devoid of history (culture); in short, devoid

of humanity, dear to colonial histography is largely posterior.Cheikh Anta Diop led throughout his life a patriotic struggle so that Africa might at long last get rid of the claws of cultural alienation which had lasted far too long, so that they would again become masters of a history which they had not lost before colonialism. "Black nations and culture" was within the context of an intense ideological struggle opposing the most awakened and conscious elements, the most politically awakened of the African elites to the tenants of colonial order who, to be witnesses to its collapse, were nonetheless less solid and untouchable.

The European Africanists schools (all tendencies mixed) were unanimous in rejecting, more often without examining, the fundamental theses of Cheikh Anta Diop relating to the "cultural unity" of Africa to the migrations which, taking their source from the original neolithic basin had ended up in the present peopling of the continent; to the continuity of the national historical past of Africans. It is that, in the eyes of some, the works of the Senegalese historian appear a dangerous precedent susceptible, like every pioneering and innovative work, to incite dangerous vocations. This concern was based on at at least one point: the disintegration by Cheikh Anta Diop of the fundamental postulates of the European Africanist discourse. Thus we read: "This false attribution of values of Egypt qualified as white to a Greece equally white reveals a deep contradiction which is not the least proof of the black origin of Egyptian civilization" (Nations Negres et Culture, page 40, Vol II, Presence Africaine, 3 em edition).

In

that fragment Cheikh Anta Diop links up the well being with the "umbilical

cord" which links "black" ancient Egypt to the rest

of the continent. similarly, the insoluble contradiction which made

that pharaonic Egypt, the mother of civilizations, does not the least

objectively belong to a continent judged to be savage, primitive and

barbarous, finally finds a rational solution.

In

that fragment Cheikh Anta Diop links up the well being with the "umbilical

cord" which links "black" ancient Egypt to the rest

of the continent. similarly, the insoluble contradiction which made

that pharaonic Egypt, the mother of civilizations, does not the least

objectively belong to a continent judged to be savage, primitive and

barbarous, finally finds a rational solution.In that regard, to measure the same time the revolutionary character of Cheikh Anta Diop's thesis and the extent of the mystification of colonial histography, let us listen to Frederich Hegel, its most qualified and profound representative: "She (Africa) is no part of the historic world, she neither shows movement nor development........., that is to say, from the north originates the Asiatic and European worlds. Cartage was in that regard an important and transient element. But it belongs to Asia a Phoenician colony. Egypt would be examined through the passage of the human mind from the east to the west, but it does not depend on the African mind." (La raison dans L'Histoirem, p 269, collection 10-18).

Through this odious falsification of history, which Karl Max qualifies a idealist, a road was made which led to the myth of anti historicity of the African continent; which continent is seen to be, in perspective of Cheikh Anta Diop, the cradle of all civilizations.

It is against such allegations, qualified rightly, by the first historian of African renaissance Cheikh Anta Diop, as "fascist" and "racist" (in the sense that they implied the incapacity of Africans to create viable political institutions), that his major work "Nations Negres et Culture", reacted. It can be deplored that his prodigious erudition, his epic style, his liberating breath had not inspired all the African intellectualls of that epoch. Worst still, African history as it is taught today in our schools does not take the Negroid dimension of ancient Egypt.

But an important question arises: in what measure do the works of Cheikh Anta Diop allow to respond to the challenges of the future? For Theophile Obenga, a disciple and a companion of the author, "with Cheikh Anta Diop, history is not defined as the study of the past of human kind, but as the construction of the future in the name of life."

Cheikh

Anta Diop was not only an intellectual, he also had a past as a man

of action who did not hesitate to embrace political militantism when

he judged it necessary. It was in that regard that he published scathing

and brilliant articles in "La voix d'Afrique", a journal

of students of the RDA (Rassemblement Democratique Africain). One

of his articles appeared in February, 1952, and already he had put

(at an epoch where most African parliamentarians opted for a policy

of compromise - not to say betrayal) on the agenda the question of

independence and the federation of the ex-colonies.

Cheikh

Anta Diop was not only an intellectual, he also had a past as a man

of action who did not hesitate to embrace political militantism when

he judged it necessary. It was in that regard that he published scathing

and brilliant articles in "La voix d'Afrique", a journal

of students of the RDA (Rassemblement Democratique Africain). One

of his articles appeared in February, 1952, and already he had put

(at an epoch where most African parliamentarians opted for a policy

of compromise - not to say betrayal) on the agenda the question of

independence and the federation of the ex-colonies.One sees it, the political doctrine of Cheikh Anta Diop, consigned to "the economic and cultural foundations", having as a philosopher's stone the notion of unity under its federal or confederal; form. A certain number of factors converged to render indispensable a political unity: the imperatives of economic independence, industrial development, the inconstances of political entities issuing from colonialism, and the cultural unity of Black Africa.

These theses, to say the truth, are neither new nor original. One remembers the iterinary of Kwame Nkrumah, almost all of whose works and, in particular the famous book entitled "Africa Must Unite", offer a brilliant illustration. Nevertheless, in the light of the political experiences of African states since 1960, one realizes that as regards the economic, political and cultural necessities of unity in order to formulate an ideology of development and liberation, they are notoriously insufficient. Such a move can only end up in a voluntarist and idealist practice which substitutes the categorical imperative of unity for contradictions and objective movements of African societies - the pseudoSenegambia Confederation is a patent example of it. Here resides one of the major contradictions which undermines the work.

In effect, no infallible mathematical law has yet demonstrated that because the ancient past of a people was brilliant, so its future must, with the fatality of bronze law equally be. Undoubtedly, it has to be underscored (and deplored) that in his persistence, by the way quite judicious, to defend the thesis of "Black Egypt", the author did not analyse the concrete social realities of the African peoples in a satisfactory way; far from being homogeneous, far from constituting the only and same group of democratic and colonized, (who were disunited by interests fundamentally antagonistic, which explain the present impasses having names such as Rwanda-Burundi, Nigeria an so on and so forth. Only these contradictions explain the relatively inefficient character of an action which, at the RDA, as at the level of the Senegalese block of masses (which later became RND - National Democratic Assembly), only realized ephemeral successes. It is now the lot of today's African generation and that of tomorrow to tap the energy emanating from the monumental heritage that Cheikh Anta Diop has bequeathed to us, to propel Africa into the first row of the international community in order to remake it as a continent of inventions and liberty. This is the challenge that the pharoah of knowledge (the ancestor of our future) has bequeathed as heritage to the African youth.

FOROYAA

(Freedom)

February, 1997

ISSN: 0796-0573

"In

practice it is possible to determine directly the skin colour and

hence the ethnic affiliations of the ancient Egyptians by microscopic

analysis in the laboratory; I doubt if the sagacity of the researchers

who have studied the question has overlooked the possibility."

"In

practice it is possible to determine directly the skin colour and

hence the ethnic affiliations of the ancient Egyptians by microscopic

analysis in the laboratory; I doubt if the sagacity of the researchers

who have studied the question has overlooked the possibility." --Cheikh Anta Diop

Cheikh Anta Diop, a modern champion of African identity, was born in Diourbel, Senegal on December 29, 1923. At the age of twenty-three, he journeyed to Paris, France to continue advanced studies in physics. Within a very short time, however, he was drawn deeper and deeper into studies relating to the African origins of humanity and civilization. Becoming more and more active in the African student movements then demanding the independence of French colonial possessions, he became convinced that only by reexamining and restoring Africa's distorted, maligned and obscured place in world history could the physical and psychological shackles of colonialism be lifted from our Motherland and from African people dispersed globally. His initial doctoral dissertation submitted at the University of Paris, Sorbonne in 1951, based on the premise that Egypt of the pharaohs was an African civilization--was rejected. Regardless, this dissertation was published by Presence Africaine under the title Nations Negres et Culture in 1955 and won him international acclaim. Two additional attempts to have his doctorate granted were turned back until 1960 when he entered his defense session with an array of sociologists, anthropologists and historians and successfully carried his argument. After nearly a decade of titanic and herculean effort, Diop had finally won his Docteur es Lettres! In that same year, 1960, were published two of his other works--the Cultural Unity of Black Africa and and Precolonial Black Africa.

During

his student days, Cheikh Anta Diop was an avid political activist.

From 1950 to 1953 he was the Secretary-General of the Rassemblement

Democratique Africain (RDA) and helped establish the first Pan-African

Student Congress in Paris in 1951. He also participated in the First

World Congress of Black Writers and Artists held in Paris in 1956

and the second such Congress held in Rome in 1959. Upon returning

to Senegal in 1960, Dr. Diop continued his research and established

a radiocarbon laboratory in Dakar. In 1966, the First World Black

Festival of Arts and Culture held in Dakar, Senegal honored Dr. Diop

and Dr. W.E.B. DuBois as the scholars who exerted the greatest influence

on African thought in twentieth century. In 1974, a milestone occurred

in the English-speaking world when the African Origin of Civilization:

Myth or Reality was finally published. It was also in 1974 that Diop

and Theophile Obenga collectively and soundly reaffirmed the African

origin of pharaonic Egyptian civilization at a UNESCO sponsored symposium

in Cairo, Egypt. In 1981, Diop's last major work, Civilization or

Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology was published.

During

his student days, Cheikh Anta Diop was an avid political activist.

From 1950 to 1953 he was the Secretary-General of the Rassemblement

Democratique Africain (RDA) and helped establish the first Pan-African

Student Congress in Paris in 1951. He also participated in the First

World Congress of Black Writers and Artists held in Paris in 1956

and the second such Congress held in Rome in 1959. Upon returning

to Senegal in 1960, Dr. Diop continued his research and established

a radiocarbon laboratory in Dakar. In 1966, the First World Black

Festival of Arts and Culture held in Dakar, Senegal honored Dr. Diop

and Dr. W.E.B. DuBois as the scholars who exerted the greatest influence

on African thought in twentieth century. In 1974, a milestone occurred

in the English-speaking world when the African Origin of Civilization:

Myth or Reality was finally published. It was also in 1974 that Diop

and Theophile Obenga collectively and soundly reaffirmed the African

origin of pharaonic Egyptian civilization at a UNESCO sponsored symposium

in Cairo, Egypt. In 1981, Diop's last major work, Civilization or

Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology was published.

Dr. Diop was the Director of Radiocarbon Laboratory at the Fundamental Institute of Black Africa (IFAN) at the University of Dakar. He sat on numerous international scientific committees and achieved recognition as one of the leading historians, Egyptologists, linguists and anthropologists in the world. He traveled widely, lectured incessantly and was cited and quoted voluminously. He was regarded by many as the modern `pharaoh' of African studies. Cheikh Anta Diop died quietly in sleep in Dakar, Senegal on February 7,1986.

You can find further information on http://www.gambia.dk/antadiop.html

Rokhaya MAIGA KA

Rokhaya Aminata Maïga Ka was born in 1940 in Saint-Louis, Senegal. Like many Senegalese, she was born into a Muslim family . Her father was a doctor, her mother a housewife and she has very happy childhood memories. Although French was spoken in her milieu, Peul, Wolof and Bambara were also spoken at home. After primary school in Kounghel and Thiès, Aminata Maïga Ka went to high school in Thiès and later to the lycée 'Eaux Claires ' in Grenoble. She later gained a Master's Degree in English at the Dakar University, followed by a stay at the universities of San Francisco and Iowa-City. Her professional career began as an English teacher at the Lycée Malick Sy in Thiès. But after completing further training in Great Britain, she filled a variety of high level posts, both with UNESCO and the government of Senegal. She has visited numerous countries during the course of her life (France, Great Britain, USA, Mali, Guinea, Mauritania, Congo and the Central African Republic) and has lived in Dakar since 1976. Aminata Maiga Ka's first publication, "La Voie du Salut - Miroir de la Vie", in 1985 was followed by "En votre nom et au mien" and "Brisures vies", as well as works on the the condition of women in Senegal and her literary critiques on the works of Mariama Bâ and d'Aminata Sow Fall. Married to the late playwright and journalist Abdou Anta Ka, she is the mother of six children. A technical adviser to the Ministry of Education, she was also a town councillor and a member of the Central Commmittee of the Socialist Party (in 1991). From 1992 to 1995, she was a Cultural Attaché at Rome's Senegalese Embassy and a representative (représentant adjoint) to the FAO, FIDA and PAM. Rokhaya Aminata Maïga Ka passed away in November 2005.

Publications

La Voie du Salut suivi de Le Miroir de la vie

[The Path of Salvation followed by Mirror of Life]. Paris: Présence

Africaine, 1985. (200p.). ISBN 2 7087 0461 3. Two short stories.

La Voie du Salut suivi de Le Miroir de la vie

[The Path of Salvation followed by Mirror of Life]. Paris: Présence

Africaine, 1985. (200p.). ISBN 2 7087 0461 3. Two short stories.The short story The Path of Salvation illustrates what little power the modern woman, initiated into the world of business and politics, actually possesses." (Back cover).

Mirror of Life describes the shameless exploitation of a young maid called Fatou: she becomes pregnant, her boyfriend betrays her and a tragic turn of events leads to her suicide. Madame Cissé, who is proud of her noble ancestry, collapses when her daughter becomes infatuated with the son of a female praise-singer. Moreover, when her son is charged with terrorist activities, her husband, who is a government minister, has to intervene in order to get him out of prison.

En votre nom et au mien [In your name and mine]. Abidjan: Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines C.I., 1989 (145p.). ISBN 2 7236 1494 8. Novel.

En votre nom et au mien [In your name and mine]. Abidjan: Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines C.I., 1989 (145p.). ISBN 2 7236 1494 8. Novel.This novel focuses on how it is that bad choices come to be made in life. Awa Gueye marries an elderly rich man, rather than the young schoolteacher whom she loves. She is encouraged in this decision by her family, who think only of the dowry they will receive. In vain, the elderly husband exhausts himself trying to satisfy his young wife. The son of the unhappy marriage, Samba, leaves school and becomes involved in drugs, which eventually cause his death. The good choices made in life form the high points of the novel and are all the more important because they are so rare.

Brisures de Vies [Fragments of Lives]. Saint-Louis du Senegal : Editions Xamal,

Brisures de Vies [Fragments of Lives]. Saint-Louis du Senegal : Editions Xamal,OUSMANE SEMBEN

Early life

The son of a fisherman, Ousmane Sembène was born in Ziguinchor in Casamance to a Lebou family. He went to an Islamic school (common for many boys in Senegal) and to the French school, learning French and basic Arabic in addition to his mother tongue, Wolof. He had to leave his French school in 1936 when he clashed with the principal. After an unsuccessful stint working with his father (Sembène was prone to sea-sickness), he left for Dakar in 1938, where he worked a variety of manual labour jobs.In 1944, Sembène was drafted into the Senegalese Tirailleurs (a corps of the French Army) in World War II and later fought for the Free French Forces. After the war he returned to his home country and in 1947 participated in a long railroad strike on which he later based his seminal novel God's Bits of Wood.

Late in 1947, he stowed away to France, where he worked at a Citroën factory in Paris and then on the docks at Marseille, becoming active in the French trade union movement. He joined the communist-led CGT and the Communist party, helping lead a strike to hinder the shipment of weapons for the French colonial war in Vietnam. During this time, he discovered writers such as Claude McKay and Jacques Roumain.

Early literary career

Sembène drew on many of these experiences for his French-language first novel, Le Docker Noir (The Black Docker, 1956), the story of Diaw, an African stevedore who faces racism and mistreatment on the docks at Marseille. Diaw writes a novel, which is later stolen by a white woman and published under her name; he confronts her, accidentally kills her, and is tried and executed in scenes highly reminiscent of Albert Camus's The Outsider. Though the book focuses particularly on the mistreatment of African immigrants, Sembène also details the oppression of Arab and Spanish workers, making it clear that the issues are as much economic as they are racial. Like most of his fiction, it is written in a social realist mode. Many critics today consider the book somewhat flawed[citation needed]; however, it began Sembène's literary reputation and provided him with the financial support to continue writing.Sembène's second novel, O Pays, mon beau peuple! (Oh country, my beautiful people!, 1957), tells the story of Oumar, an ambitious black farmer returning to his native Casamance with a new white wife and ideas for modernizing the area's agricultural practices. However, Oumar struggles against both the white colonial government and the village social order, and is eventually murdered. O Pays, mon beau peuple! was an international success, giving Sembène invitations from around the world, particularly from Communist countries such as China, Cuba, and the Soviet Union. While in Moscow, Sembène had the opportunity to study filmmaking for a year at Gorki Studios.

Sembène's third and most famous novel is Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu (God's Bits of Wood, 1960); most critics consider it his masterpiece, rivaled only by Xala. The novel fictionalizes the real-life story of a railroad strike on the Dakar-Niger line that lasted from 1947 to 1948. Though the charismatic and brilliant union spokesman, Ibrahima Bakayoko, is the most central figure, the novel has no true hero except the community itself, which bands together in the face of hardship and oppression to assert their rights. Accordingly, the novel features nearly fifty characters in both Senegal and neighboring Mali, showing the strike from all possible angles; in this, the novel is often compared to Émile Zola's Germinal.

Sembène followed Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu with the (1962) short fiction collection Voltaïque (Tribal Scars). The collection contains short stories, tales, and fables, including "La Noire de..." which he would later adapt into his first film. In 1964, he released l'Harmattan (The Harmattan), an epic novel about a referendum for independence in an African capital.

Later literary career

With the 1965 publication of Le mandat, précédé de Vehi-Ciosane (The Money Order and White Genesis), Sembène's emphasis began to shift. Just as he had once vociferously attacked the racial and economic oppression of the colonial government, with this pair of novellas, he turned his sights on the corrupt African elites that followed.Sembène continued this theme with the 1973 novel Xala, the story of a El Hadji Abdou Kader Beye, a rich businessman struck by what he believes to be a curse of impotence ("xala" in Wolof) on the night of his wedding to his beautiful, young third wife. El Hadji grows obsessed with removing the curse through visits to marabouts, but only after losing most of his money and reputation does he discover the source to be the beggar who lives outside his offices, whom he wronged in acquiring his fortune.

Le Dernier de l’empire (The Last of the Empire, 1981), Sembène's last novel, depicts corruption and an eventual military coup in a newly independent African nation. His paired 1987 novellas Niiwam et Taaw (Niiwam and Taaw) continue to explore social and moral collapse in urban Senegal.

On the strength of Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu and Xala, Sembène is considered one of the leading figures in African postcolonial literature. However, the lack of English translation of many of his novels has hindered Sembène from achieving the same international popularity enjoyed by Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka.

Film

As an author so concerned with social change, one of Sembène's goals had always been to touch the widest possible audience. After his 1960 return to Senegal, however, he realized that his written works would only be read by a small cultural elite in his native land. He therefore decided at age 40 to become a film maker, in order to reach wider African audiences.In 1963, Sembène produced his first film, a short called Barom Sarret (The Wagoner). In '64 he made another short entitled Niaye. In 1966 he produced his first feature film, La Noire de..., based on one of his own short stories; it was the first feature film ever released by a sub-Saharan African director. Though only 60 minutes long, the French-language film won the Prix Jean Vigo,[1] bringing immediate international attention to both African film generally and Sembène specifically. Sembène followed this success with the 1968 Mandabi, achieving his dream of producing a film in his native Wolof.[1] Later Wolof-language films include Xala (1975, based on his own novel), Ceddo (1977), Camp de Thiaroye (1987), and Guelwaar (1992). The Senegalese release of Ceddo was heavily censored, ostensibly for a problem with Sembène's paperwork, but more probably for its anti-Muslim themes. However, Sembène distributed fliers at theaters describing the censored scenes and released it uncut for the international market. In 1971, Sembène also made a film in the Diola language and French entitled Emitai.

In 1977, he was a member of the jury at the 27th Berlin International Film Festival.[2]

Recurrent themes of Sembène's films are the history of colonialism, the failings of religion, the critique of the new African bourgeoisie, and the strength of African women.

His final film, the 2004 feature Moolaadé, won awards at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival[3] and the FESPACO Film Festival in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. The film, set in a small African village in Burkina Faso, explored the controversial subject of female genital mutilation.

Death

Ousmane Sembène died on June 9, 2007, at the age of 84. He had been ill since December 2006, and died at his home in Dakar, Senegal where he was buried in a shroud adorned with Quranic verses.[4] Sembène was survived by three sons, from two marriages.[5]Seipati Bulane Hopa, Secretary General of the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) described Sembène as "a luminary that lit the torch for ordinary people to walk the path of light...a voice that spoke without hesitation, a man with an impeccable talent who unwaveringly held on to his artistic principles and did that with great integrity and dignity."[6]

South Africa's Dr. Z. Pallo Jordan, Minister of Arts and Culture, went further in eulogizing Sembène as "a well rounded intellectual and an exceptionally cultured humanist...an informed social critic [who] provided the world with an alternative knowledge of Africa."[6]

Works

Books

- Le Docker noir (novel) - Paris: Debresse, 1956; new edition Présence Africaine, 2002; trans. as The Black Docker, London: Heinemann, 1987.

- O Pays, mon beau peuple! (novel) - 1957

- Les bouts de bois de Dieu (novel) - 1960; trans. as God's Bits of Wood, London: Heinemann, 1995.

- Voltaïque (short stories) - Paris: Présence Africaine, 1962; trans. as Tribal Scars, Washington: INSCAPE, 1975.

- L’Harmattan (novel) - Paris: Présence Africaine, 1964.

- Le mandat, précédé de Vehi-Ciosane - Paris: Presence Africaine, 1966; trans. as The Money-Order with White Genesis, London: Heinemann, 1987.

- Xala, Paris: Présence Africaine, 1973.

- Le dernier de l'Empire (novel) - L'Harmattan, 1981; trans. as The Last of the Empire, London: Heinemann, 1983; "a key to Senegalese politics" - Werner Glinga.

- Niiwam - Paris: Presence Africaine, 1987; trans. as Niiwam and Taaw: Two Novellas (Oxford and Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 1992).

Selected filmography

- Borom Sarret (1963)

- Niaye (1964)

- La Noire de...(1966)

- Mandabi (1968)

- Xala (1975)

- Ceddo (1977)

- Camp de Thiaroye (1988)

- Guelwaar (1992)

- Faat Kiné (2000)

- Moolaadé (2004)

Further reading

- Gadjigo, Samba. Ousmane Sembène: Dialogues with Critics and Writers. Amherst: University of Massachusestts Press, 1993.

- Murphy, David. Imagining Alternatives in Film and Fiction - Sembene. Oxford: Africa World Press Inc., 2001.

- Niang, Sada. Littérature et cinéma en afrique francophone: Ousmane Sembène et Assia Djebar. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996.

- Niang, Sada & Samba Gadjigo. "Interview with Ousmane Sembene." Research in African Literatures 26:3 (Fall 1995): 174-178.

- Vieyra, Paulin Soumanou. Ousmane Sembène cineaste: première période, 1962–1971. Paris: Présence Africaine, 1972.

- Pfaff, Françoise. The Cinema of Ousmane Sembene: A Pioneer of African Film. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1984.

- Annas, Max & Busch, Annett: Ousmane Sembene: Interviews. University Press, Mississippi, 2008.

References

- Los Angeles Times "Ousmane Sembene, 84; Sengalese hailed as 'the father of African film'" June 14 2007

- "Berlinale 1977: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- "Festival de Cannes: Moolaadé". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- Callimachi, Rukmini "Father of African cinema buried in Senegal" June 12, 2007.

- Macnab, Geoffrey (2007-06-13). "Obituaries - 'Ousmane Sembene'". The Independent. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- www.screenafrica.com | news | stop press Tributes to Ousmane Sembene: 1923 – 2007

Informations extracted frome: WIKIPEDIA

Ousmane Sow was born in Dakar in 1935. His father, from Dakar, was thirty years older than his mother, who was from Saint-Louis. He grew up in Reubeuss, one of the liveliest areas of Dakar, where he received a very strict education and was given responsibilities at a very early age by his father. From his father he inherited discipline, a sense of duty, disdain for honours and a free spirit. When his father died, despite his great attachment to his mother, he decided to leave for Paris without a penny in his pocket. He was put up in police stations and discovered the gentler side of a France that was still a welcoming place. While working at various odd jobs, and having given up his courses at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, he obtained a diploma in physiotherapy.

Although he had been sculpting since childhood, it was not till he was fifty that Ousmane Sow made sculpture his full-time profession. However his previous experience as physiotherapist can be seen in the magnificent sense of anatomy evident in his work. In the evenings throughout all those years, he would transform his consulting room and his successive apartments into sculpture studios. He would then destroy or leave behind the works he created.

Up to the time of his first exhibition, which was organized by the French Cultural Center in Dakar in 1987, nothing was known of his work, apart from an excerpt from an animated film, which portrayed small sculptures. Only six years after this first exhibition in Dakar, he exhibited his work at Dokumenta in Kassel, Germany. In 1995, the Seated Nouba and Standing Nouba closed the exhibition organized in Venice at the Palazzo Grassi for the Centenary of the Biennale.

In 1984, inspired by Leni Riefenstahl's photographs of the Noubas of Southern Sudan, he began to work on the wrestlers of this ethnic group and produced his first series of sculptures, The Nouba. In 1988, he created The Masai, in 1991 The Zulus, and in 1993 The Peulh.

In 1991 he bought the land on which to build his house, designed from his imagination. The walls and tiles are completely covered with his own sculpting media and the house symbolises the Sphinx, foreshadowing his future series of sculptures entitled The Egyptians.

In the courtyard of this house, he produced The Battle of Little Big Horn, a series of thirty-five pieces. The pieces were first exhibited in Dakar in January of 1999 and served as a preview to the Paris exhibition on the Pont des Arts, which featured all his series of sculptures and attracted over three millions visitors.

In 2001, he commissioned the Courbertin and Susse Foundries to produce three bronzes from his originals: The Dancer with Short Hair (Nouba series), The Standing Wrestler (Nouba series) and Mother and Child (Masai series). The three pieces were exhibited in the Spring of 2001 at the Dapper Museum in Paris.

Since then, « The Thrower » (Zulu series) and « Sitting Bull at prayer » (Little Big Horn series) have been produced.

In the same year, he carried out a commission for the International Olympic Commitee, « The runner at the start line ».

During the summer of 2002, at the request of « Medecins du Monde », he created a sculpture of Victor Hugo for the « Rejection of poverty and exclusion day ».

The bronze of this sculpture was commissioned by the city of Besançon, Victor Hugo ‘s native city. It was erected on October 17, 2003, in the Place des Droits de l’Homme to mark « Rejection of poverty and exclusion day » in the presence of Medecins du Monde.

During 2003, the Whitney Museum in New York also presented part of the Little Big Horn Series as part of an exhibition entitled « The american effect ».

Ousmane Sow has always sculpted without a model. He creates his own medium. In a form of subtle alchemy, he allows a number of ingredients to macerate over the years. For him this medium is a work in itself, giving him almost as much pleasure as creating the sculpture itself. He applies this material onto a framework of metal, straw and jute, allowing Nature and the medium their own freedom thus opening of the door to the unforeseen. This approach is inherently artistic, but also African.

Today his life and his work are deeply anchored in his country. He cannot imagine himself sculpting anywhere other than Senegal. Although he lived for more than twenty years in France, nothing and nobody could ever entice him to leave his native African soil.`

YOUSSOU NDOUR

N'Dour was born in Dakar to a Serer father. At age 12, he began to perform and within a few years was performing regularly with the Star Band, Dakar's most popular group during the early 1970s. Several members of the Star Band joined Orchestra Baobab about that time.

Despite N’Dour's maternal connection to the traditional griot caste, he was not raised in that tradition, which he learned instead from his siblings. His parents' world view encouraged a modern outlook, leaving him open to two cultures and thereby inspiring N'Dour's identity as a modern griot.

Career

In 1979, he formed his own ensemble, the Étoile de Dakar. His early work with the group was in the Latin style popular all over Africa during that time. In the 1980s he developed a unique sound with his ultimate group, Super Étoile de Dakar featuring Jimi Mbaye on guitar, bassist Habib Faye, and Tama (talking drum) player Assane Thiam.By 1991 he had opened his own recording studio, Xippi, and, by 1995, his own record label, Jololi.

N'Dour is one of the most celebrated African musicians in history. His mix of traditional Senegalese mbalax with eclectic influences ranging from Cuban rumba to hip hop, jazz and soul won him an international fan base of millions. In the West, N'Dour collaborated with Peter Gabriel,[3] Axelle Red,[4] Sting,[5] Alan Stivell,[6] Bran Van 3000,[7] Neneh Cherry,[8] Wyclef Jean,[5] Paul Simon,[8] Bruce Springsteen, Tracy Chapman, Branford Marsalis, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Dido and others.

The New York Times described his voice as an "arresting tenor, a supple weapon deployed with prophetic authority".[9] N'Dour's work absorbed the entire Senegalese musical spectrum, often filtered through the lens of genre-defying rock or pop music from outside Senegalese culture.

In July 1993, an African opera composed by N'Dour premiered at the Opéra Garnier for the French Festival Paris quartier d'été.

He wrote and performed the official anthem of the 1998 FIFA World Cup with Axelle Red "La Cour des Grands".[4]

Folk Roots magazine described him as the African Artist of the Century. He toured internationally for thirty years. He won his first American Grammy Award (best contemporary world music album) for his CD Egypt in 2005.[citation needed]

He is the proprietor of L'Observateur, one of the widest-circulation newspapers in Senegal, the radio station RFM (Radio Future Medias) and the TV channel TFM.

In 2006, N'Dour played the role of the African-British abolitionist Olaudah Equiano in the movie Amazing Grace, which chronicled the efforts of William Wilberforce to end slavery in the British Empire.[10]

In 2008, N'Dour offered one of his compositions, Bébé, for the French singer Cynthia Brown.[citation needed]

In 2011, N'Dour was awarded an honorary doctoral degree in Music from Yale University.[11]

Activism

N'Dour was nominated Goodwill Ambassador of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) on 16 October 2000.[12]In Senegal, N'Dour became a powerful cultural icon, actively involved in social issues. In 1985, he organized a concert for the release of Nelson Mandela. He was a featured performer in the 1988 worldwide Amnesty International Human Rights Now! Tour collaborating with Lou Reed on a version of the Peter Gabriel song Biko which was produced by Richard James Burgess and featured on the Amnesty International benefit album The Secret Policeman's Third Ball. He worked with the United Nations and UNICEF, and he started Project Joko to open internet cafés in Africa and to connect Senegalese communities around the world. He performed in three of the Live 8 concerts (in Live 8 concert, London, Live 8 concert, Paris and at the Live 8 concert, Eden Project in Cornwall) on 2 July 2005, with Dido.[13] He covered John Lennon's "Jealous Guy" for the 2007 CD Instant Karma: The Amnesty International Campaign to Save Darfur. He appeared in a joint Spain-Senegal ad campaign to inform the African public about the dramatic consequences of illegal immigration.[citation needed] N'Dour participated in the Stock Exchange of Visions project in 2007.[14]

In 2007 he became a council member of the World Future Council.[citation needed]

Since 2008, he is a member of the Fondation Chirac's honour committee[15]. The same year, Youssou N'Dour's microfinance organization named Birima was launched with the collaboration of Benetton United Colors.

In 2009, he released his song "Wake Up (It's Africa Calling)" under a Creative Commons license to help IntraHealth International in their IntraHealth Open campaign to bring open source health applications to Africa. The song was remixed by a variety of artists including Nas, Peter Buck of R.E.M., and Duncan Sheik to help raise money for the campaign.[16]

Politics

At the beginning of 2012, he entered the race for the presidency of Senegal for the 2012 presidential election, competing against Abdoulaye Wade[17][18]. However, he was disqualified from running in the election over the legitimacy of the signatures he had collected to endorse his campaign[19].In April 2012 it was announced that N'dour has been appointed tourism and culture minister in the cabinet of new Prime Minister Abdoul Mbaye.

Source: Wikipedia .

Xalam (band)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Xalam is the name of a Senegalese musical group founded in 1969 founded by a group of friends. The band was originally called African Khalam Orchestra.The band takes its name from the lute-like instrument the xalam. Xalam performed a mix of contemporary jazz tunes as well as African originals, usually sung in Wolof, the dominant local language. The band included sax, drums, African percussion, bass and electric guitar.

Xalam started playing dance music, such as Rock, Salsa, Bossa, and Rhythm and Blues. The group performed in Senegal and other countries in Africa. Numerous musicians have played in the group and through their collaboration, have become very popular.

In 1975 they went on an African tour with Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba. Later, the group decided it was time to find its own musical identity and left the stage for four years to look for inspiration in traditional folk music and mix it with their own modern music.

In 1979, Xalam made a guest appearance at the Berlin Horizonte Festival. That first trip to Europe was their opportunity to record their first LP: Ade.

In 1981, Xalam recorded music for the soundtrack of the Epcot African Pavilion videotape in Dakar for the Disney Corporation, to be used at their Epcot site in the US. They also performed at the Dakar Jazz Festival and jammed with Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, Dexter, Sonny Rollins, and others. In the early 1980s, the band moved to Paris, where they became regulars on the local music scene. Prosper died in the mid-1980s, replaced on drums by his younger brother, who had been the drummer for Senemali, another Senegalese group which had moved to Amsterdam.

In June 1982, the group was revealed to the French public at Paris Africa Fête. Then, band recorded the following LP, Gorée, in London. The band was so impressive that the Rolling Stones invited the percussionists to play on their next album Undercover of the Night.

A European tour followed in 1983, Xalam opened for Crosby, Stills & Nash in Paris (Hippodrome d’Auteuil) in front of 20,000 people. With the release of the LP Gorée, the album reached the Top 5 (African, Reggae, and Folk albums) published in Le Monde for five months.

1984 found the band writing the music for the French movie "Marche à l’Ombre" (over 5,000,000 spectators), followed by 150 concerts starting in Switzerland and ending in Paris.

Xalam opened for Robert Plant at the Palais des Sports in Paris, France, in 1985.

In 1986, they performed 3 concerts at the Cirque d’Hiver, then continued on an international tour of more than a hundred gigs to support the release of Apartheid, including the Francofolies of La Rochelle, the Festag in Guadeloupe, and a long winter tour in Africa.

A Canadian tour followed in 1987, including Montreal, Toronto, Québec, etc. Xalam also performed at the Printemps de Bourges in France and then recorded the LP Xarit in Paris.

1988 was a busy year with a Parisian concert at The Wiz, a performance at the Paris Africa Fête, then a show in Geneva, Switzerland (in front of 30,000 people), to aid the Helping Hand Cooperation for the N’Dem village in Senegal. The LP Xarit was released, followed by a tour of Austria, Tunisia (Carthage Festival), and Japan (Osaka, Sapporo, Tokyo and Ngoya) with resounding success. Then, they performed at the Anti-Apartheid Night: "Hommage à Nelson Mandela" in Paris, at the Champ de Mars (in front of 25,000 people), and a concert at Montreux Casino.

Between 1989 and 1992, Xalam played various concerts and venues including The Midem in Cannes: concert at the Hotel Martinez, 2 concerts at the New Morning and La Cigale in Paris; a tour of Africa in 1990, then 2 concerts at the Auditorium des Halles, Paris; in 1991, a tour of Switzerland and Germany, and back to Switzerland for ten gigs, before recording the next LP Wam Sabindam.

A 1993 French tour warmed up the public for the release of Wam Sabindam in September, followed by a Swiss tour (Arthur’s Club, Emmenthaler Thoune, Le Locle, Chapiteau Sambaille), and another in the spring of 1994 (Case à Chocs, Albani, Bus Stop, Mad, Kantonsschule, Mühle Hunziken). They were off to the US that summer, performing at the 25th Anniversary Woodstock Festival (in front of more than 500,000 people), and an English tour, including the Heathrow Festival.

After a few shows in 1995 (i.e. Festival in Senegal with RFI (Radio France; the French Cultural Center), the band took a long-needed break.

Xalam returned to the stage in 1999 in Switzerland for Le Locle Jazz Festival; a 2001 club tour in Paris, France (Baiser Salé, Petit Journal Montparnasse, etc.); a 2002 European Tour (Belgium, Switzerland, France); a Festival Tour in France in 2003; and a tour of France and Spain in 2004.

The band took another break, with some members leaving to pursue various solo projects (i.e. Taffa composing and playing with Jean-Luc Ponty, for theatrical pieces and clinics; Brahms with Manu Chao, Cheikh producing, composing and arranging with local musicians in Dakar; Henri producing and arranging, as well as managing the Quai des Arts in St. Louis, Senegal; Baye becoming involved planning events at a music center in Saint Germain en Laye, France, while playing with a Jazz trio; Souleymane leading a successful solo career in Dakar).

Recently, in the fall of 2008 and the spring of 2009, the band succeeded in realizing their grand comeback, with concerts in Dakar Senegal (Just4You, St. Louis Jazz Festival, Iba Mar Diop Stadium) and Burkina Faso. The reunion tour coincided with the re-release of Apartheid on CD and the first-time release of perhaps their best live performance, the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1991 (Live à Montreux) on CD, as well as a Best of 2-CD set [2A@Z], on which all tracks were entirely remastered.

Xalam is presently working on a new studio CD, and a DVD release of the 29 April 2009 show at Iba Mar Diop Stadium. They are also continuing to tour, with recent dates in Lebanon and Johannesburg, South Africa in September/October 2009, as well as in Dakar, where they are presently, working on new concert dates and projects.

April 2010 ushers in the 50th Anniversary of the Independence of Senegal and some special concerts/gala evenings for Xalam in Dakar, Saint-Louis, South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Thione Seck

Thione Ballago Seck (born March 12, 1955) is one of Senegal's greatest singers and musicians in the mbalax genre, on par with Baaba Maal and Youssou N'dour although he hasn't achieved the same level of fame outside his country. Seck comes from a family of "griot" singers from the Wolof people of Senegal. His first job was with Orchestre Baobab, but he later formed his own band, Raam Daan, which he still heads.

Seck's album Orientation was one of four nominated for BBC3 Radio's World Music Album of the Year in 2006. In much of his music, and notably on this album, Seck experiments with the use of Indian & Arabic scales. This supplements his laid back vocals and the band's intense sabar driven rhythms, and displaces the band's more usual guitars, horns, and synthesizers. This album was made in collaboration with a range of more than 40 North African, Arab, and Indian musicians, playing diverse instruments and creating a fusion of styles. Seck has stated that Bollywood films were a longstanding musical influence for him, and the experiment in a fusion style reflects this.

OMAR PENE

is the emblematic lead singer of the Super Diamono.[1] He was born in the working-class neighborhood of Derkle, in 1956. In the mid 1970s (1975–1976), he joined the Super Diamono, one of the longest running Senegalese popular bands- just as the Orchestra Baobab and the Super Etoile of Dakar. Recruited by Bailo Diagne, the first bass-player and a founding member of the group, Pene stood out as the most natural fixture in the band.

Along with his band members Bassirou Diagne, Bob Sene, Aziz Seck, Lapa Diagne, Adama Faye, Abdou Mbacke and shortly after, Ismael Lo - already known as 'l’homme orchestre' (one man band) due to his solo performances - they helped shape Senegalese contemporary music.[1] During the 1980s, in Dakar, there were two dominant types of melomanes, the ones bitten by the frenetic and highly syncopative Mbalax of the Super Etoile, who frequented Djender and later on Thiossane night club, and those who religiously consumed the progressive bluesy-funky- soulful brand of local fusion of Super Diamono- who filled the Balafon Club located in the other side of town, near the Port Autonome de Dakar. Although Omar Pene and Youssou Ndour, always maintained an healthy and lively artistic competition, their supporters pledged a loyalty only seen among opposing football fans (soccer). In many ways, both used the Mbalax, which is almost unavoidable, once the Sabar is involved, but they did it differently.

Over the years many of the group’s original members went on to other things, Omar Pene stayed; and to this day- even as he is now enjoying his solo journey he uses the Super Diamono, and what ever that is left of it, as a backup band. Omar Pene established himself as a “conscious singer,” instead of indulging in praise songs- as many of his contemporaries did in honor of the riches and famous, he maintained a repertoire of socially engaged and sensitive songs. To this date, he has released dozens of hits in more than thirty albums and cassettes.

source from wikipedia

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario